Eikland Energy Analysis: The U.S. DOE LNG export moratorium and a case for a 200 mtpa export ceiling

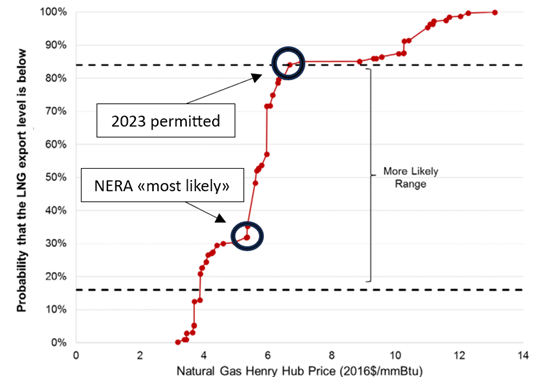

The announcement of a moratorium on the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) awarding new LNG export permits (including extensions) on January 22, 2024, has stirred dissatisfaction among project developers and potential LNG buyers. Until mid-2023, both FTA and non-FTA permitting had been relatively straightforward, with applicants relying on the conclusions of the 2018 DOE-commissioned NERA study “Macroeconomic Outcomes of Market Determined Levels of U.S. LNG Exports” to bolster their applications. Licensing nearly 50 Bcf/day of natural gas for LNG exports, equivalent to over 50% of U.S. dry gas production, the DOE essentially anticipated that the market would self-regulate to a reasonable and acceptable level. It now seems clear that something has to be done.

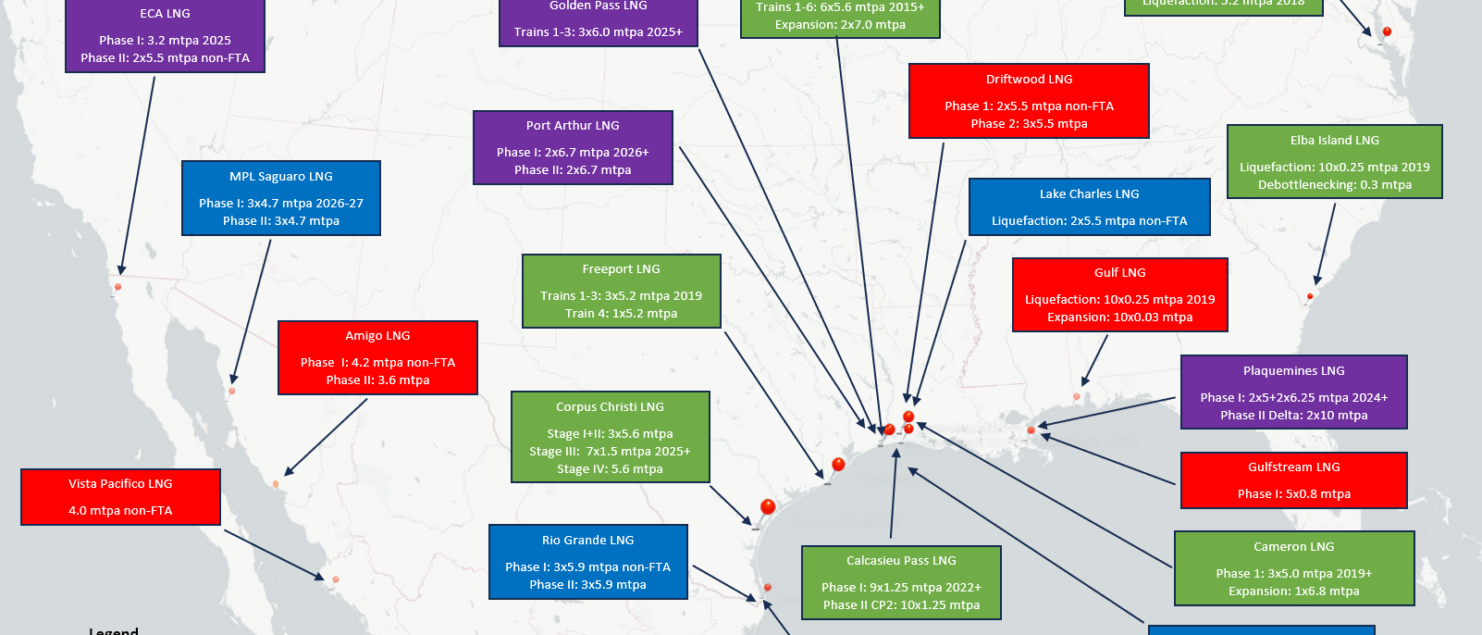

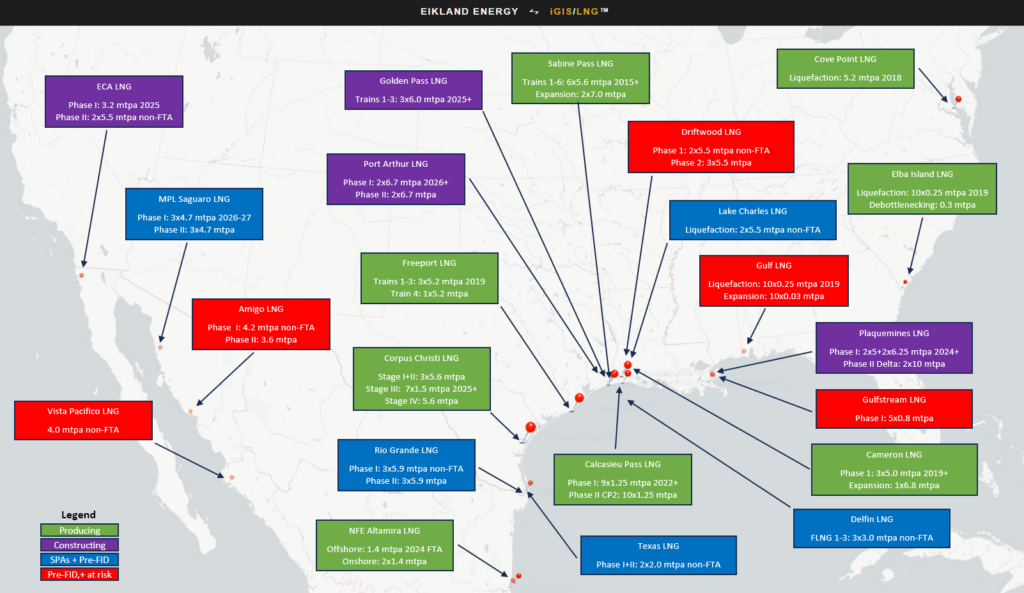

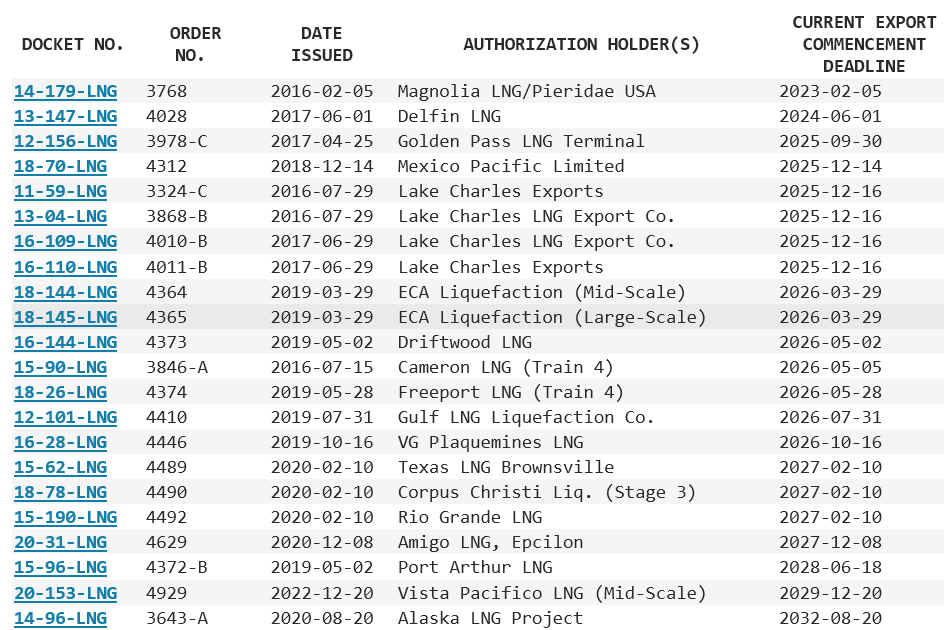

The NERA study indicated that the most likely LNG export levels, 100 mtpa in 2030 and 150 mtpa in 2040 (measured as plant feedgas), would not significantly impact natural gas prices and would have positive effects on the U.S. GDP across most of the 56 different scenarios considered. However, the most likely LNG export level for 2030 had already been surpassed in 2023 (despite a 9-month closure of Freeport LNG following the June 7, 2022, explosion). Alongside export permit increases from debottlenecked plants in 2023 (adding 5-10%) and projects currently under construction, LNG exports are expected to reach NERA’s most likely level for 2040, 150 mtpa, by mid-2026. This expansion will be driven by the initiation of Calcasieu Pass LNG blocks 8-9, Plaquemines LNG, Golden Pass LNG, Port Arthur LNG Phase I and Corpus Christi Stage III, as well as ECA LNG Phase I and NFE Altamira FLNG I.

The growth in exports has already had market consequences. Since 2021, several extreme weather events in Texas and Louisiana have demonstrated that large and inflexible LNG exports have contributed to energy price spikes and power outages. This suggests that the price-triggering upper bounds of the NERA scenarios have been reached at the margin. Further growth in LNG exports could, without mitigating measures, increase the frequency of such events. Already, Freeport LNG near Houston has agreed to relinquish power or natural gas on market demand. The chart below illustrates NERA’s 2018 price response curve across scenarios with annotations from Eikland Energy.

The price spikes and outages have unsettled U.S. consumers and provide important context for the 2024 DOE moratorium on new LNG export permitting, extending beyond assessments of shale gas resource availability and environmental impacts. The laissez-faire conclusions of the NERA study will undergo close scrutiny this year, as it appears evident that some tightening is necessary. Without access to new permits or the option of extending permit deadlines for project startups, there could naturally be a reduction in the current U.S. export portfolio. Several projects have already implemented protective measures.

The present analysis offers a review of the project portfolio, an assessment of a sustainable level for U.S. LNG exports, and implications moving forward. The supporting data includes information from the Eikland Energy iGIS/LNG database and official project filings. We anticipate that fully DOE-permitted projects such as Driftwood LNG I&II, Texas LNG I&II, Gulf LNG, Freeport LNG Train 4, and possibly Delfin LNG FLNG 1 and NFE’s Louisiana LNG will struggle to make sufficient progress towards a final investment decision (FID) in 2024. We also reserve judgment on the ability of more advanced projects such as Cameron LNG Train 4, Corpus Christi Stage IV, Lake Charles LNG, Port Arthur LNG Phase II, and potentially NFE’s Altamira FLNG II&III onshore to reach FID in 2024. The risk for several projects is that they will require startup deadline extensions from the DOE and consequently be directly affected by the moratorium.

Projects like Sabine Pass LNG Stage 5, Gulfstream LNG, Delfin LNG (FLNG 2-4), Alaska LNG, and ECA LNG Phase II are 2-3 years outside of the immediate development and FID timeline. The same may be said for Venture Global’s large CP2 LNG project (Calcasieu Pass LNG extension), which, despite strong buyer interest, faces environmental mitigation hurdles. There is also speculation that conflicts over the commercial operation date (COD) at Calcasieu Pass LNG, also a Venture Global project, could affect CP2 and possibly its subsequent Delta LNG project (Plaquemines LNG extension).

However, aided by severe Panama Canal drought problems, there is strong buyer interest in projects based on U.S. gas exports via LNG from Mexico’s west coast. Mexico Pacific LNG I & II, which are fully permitted, have shown significant development in 2023, and an FID is likely. These projects, along with similar ones, are less likely to affect the U.S. gas balance and prices as they are based on shale gas from the Permian. We also anticipate that the DOE will find Elba Island LNG debottlenecking and capacity expansion from 2.5 to 2.8 mtpa unproblematic, despite not yet having applied for an increase in the existing non-FTA export permit.

Magnolia LNG remains deeply challenged, and the G2 LNG, Pointe LNG, Fourchon/Argent LNG, and Monkey Island LNG projects have been formally or effectively terminated over the past 2-3 years due to lack of market interest. These are therefore not included on the project map. The projects listed above represent roughly 3×50 mtpa of uncertain, delayed, or canceled LNG export capacity additions. The key observation is that the “unconstrained probable” export capacity level for 2030 exceeds the level indicated by the NERA study that would trigger larger price rises. We, therefore, expect new and updated “cumulative impact” market studies for the DOE in 2024 to indicate conditions and a ceiling level for sustainable U.S. Lower-48 LNG exports (i.e. excluding Alaska).

Our current assessment for a prudent, balanced, and consumer-accepting Lower-48 U.S. LNG export ceiling for 2030 is around 200 mtpa, which is still more than double the 2023 actual export level. This suggests that at most only 25-35 mtpa of incremental Lower-48 export capacity can be granted. The ceiling export level would then absorb approximately 26 Bcf/day of feedgas to liquefaction plants, equivalent to 25% of the 2023 U.S. dry natural gas production of 103 Bcf/day. “Firm” exports at this level make it likely, in our view, that the tail will occasionally wag the dog.

The U.S. Annual Energy Outlook projects flat domestic natural gas demand through 2040. LNG feedgas levels and plant availability are already closely monitored by the market, and having LNG exports rise to the indicated levels will further affect Gulf Coast and national daily and within-day market balances. Unexpected drops in LNG exports also put pressure on prices. Since shale gas production is inherently inflexible and supply lines long, to limit the risk of price spikes, LNG plants could be required, as part of mitigating measures, to release feedgas (or supply power) to help meet market balancing requirements.

The background for the current LNG export permitting moratorium is indeed complex. The U.S. is not prepared for domestic volatilities caused by LNG trade and conversely, as Shell also states in its 2024 LNG Outlook published on 14 February, the global gas market is increasingly exposed to U.S. risks. Events unfolding in 2024 will contribute to forming conclusions, and it’s premature to predict outcomes at this early stage. However, some major LNG buyers already see a peak in U.S. LNG export capacity beyond 2030 and have started to look to supplemental LNG sources sources. On their side U.S. energy traders are already increasingly focusing on capturing short-term LNG plant utilization and global LNG dynamics as part of domestic balances.

Postscript: On 26 February 2024 the U.S. DOE published an explanatory update and further details on the background and objectives of the LNG export moratorium. We have concluded that the new document corroborates the basis for our analysis above and find that there is at this time no need for reassessment of our conclusions. The explanatory update undoubtedly comes in response to (expected) critisisms and the terseness of the original January 22 White House statement.