LNG ADPs 2018-20: Surplus vs Strategy

The next three years will see 30+ mt annual firm increases in LNG capacity and a large supply overhang. Only major utilisation of spare regasification capacity in China and Europe can absorb the increases to avoid significant downward price pressure. Such capacity utilisation is unlikely. This “Burning Issues” identifies additional risks of price drops due to production programming overcommitments and operational distress volumes for lack of market offtake flexibility. The companies that principally face these changes are identified. We then develop the business play, and outline essential steps towards strong LNG business strategies and resilient value chains in a competitive and fast-moving market. Increased business adroitness with deep and flexible storage and modulation capabilities for the 1-12 month horizon are the key capabilities that will characterise LNG operators in the years ahead, whether the focus is global or regional.

Setting the Scene: The extent of excess LNG supply 2018-20

The net increase in LNG export capacity and supply was about 20 mtpa (million metric tonnes per annum) in 2015 and 2016. This included capacity additions from debottlenecking, equivalent to about 5 mtpa. The market absorbed the incremental volumes through a combination of 1-train equivalent/4 mtpa lower production from Trinidad, increased power sector use and colder, more normal northern hemisphere winter and demand for 2016/17, and some reduced offtake under certain high-priced contracts.

Even after indefinite postponements of several FLNG projects, the increase in LNG export capacity and supply will conservatively average around 30 mtpa from mid-year 2017 to mid-year 2020. Supply from Trinidad seems set to stabilise, and there may be added elsewhere supply from debottlenecking and increased capacity utilisation. In Egypt, the rapid tie-in of large gas discoveries, like Zohr, could lead to at least one LNG train reactivation in the period.

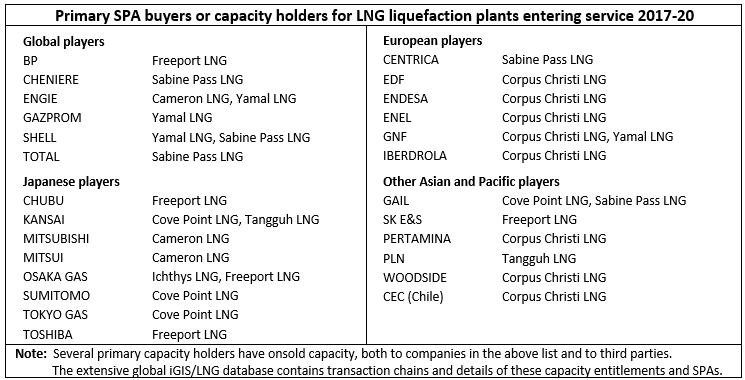

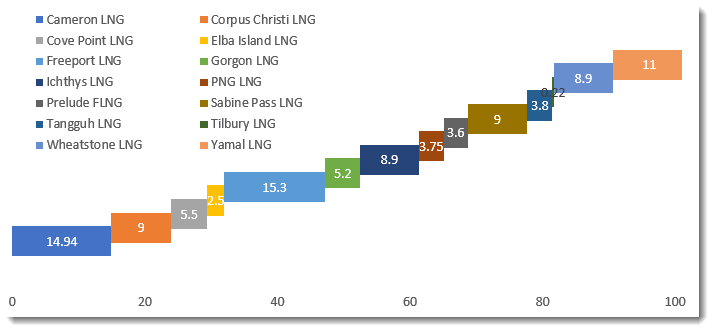

Global LNG liquefaction capacity additions for completion 2017-2020 (mtpa).

Source: Eikland Energy iGIS global natural gas and LNG DB.

- Other far-advanced projects, sanctioned or recently postponed, may add substantial capacity at the end of the triennium.

- De-bottlenecking expansions often add 10% to initial design capacity.

- All projects have SPAs with payment obligations, but many provide significant volumetric flexibility.

The completion of major pipelines from US to Mexico (2017-18); Nordstream II (Russia-Europe), Turkstream (Russia-Turkey/the Balkans), and the Power of Siberia (Russia-China) – scheduled for 2019-20, bring competitive gas to key LNG markets that can marginally displace LNG. Russia has historically realised major projects in the face of adverse market conditions, and current updates demonstrate this. At the same time, it is unlikely that decline in conventional gas could be sufficiently substantial to provide balancing support.

Higher coal prices, UK environmental price support, Dutch gas production curtailments and a relatively normal winter of 2016/17 brought additional demand that may not be repeated. The current phase of La Niña also makes drought in Spain and Brazil, and low river water levels in France (limiting cooling capacity of nuclear plants) less likely. Balancing the surplus, therefore, requires “true” demand, e.g. in Pakistan and Bangladesh, and activation of highly price-sensitive power demand in Western Europe and north-east Asia, where spare regasification capacity is ample. Unfortunately, increasingly low cost renewables, not coal, becomes to competition to beat.

Problem Looming: Setting Annual Delivery Programmes with unresolved demand

The scenario outlook is one of looming LNG supply overhang, in our estimate more than 50 percent above incremental firmed-up demand, and there is presently only a moderate chance of plant start-up delays that could “alleviate” the situation. Even the case of persistent train outages would not alter the fundamental assessment.

As we now move through spring and summer, key capacity holders must nominate and decide on first tranches of LNG volumes from several new LNG trains. This could become such a major physical and commercial challenge that radical measures may be necessary for some.

In parallel, suppliers and developers will rush to complete facilities and execute mandated tests, including capacity tests. It may be a risk that unnotified simultaneous “must flow” commissioning requirements may lead to unexpected market stresses, such as when the 25.5 bcma Langeled pipeline from Norway caused negative system marginal prices in the UK a decade ago. (Langeled’s upstream capacity increases in 2017 by the equivalent of a 5m mtpa LNG train, as part of tie-in of the new Norwegian Sea Gas Infrastructure (“NGIS”) pipeline).

Legacy LNG contract commitments along with lack of transparency and broad-based liquidity in the market will make it difficult for several companies to find a feasible resolution to balancing supply and demand. While there will be the expiry of several old long-term SPA’s in the period that could formally balance supply and demand, there is still substantial delivery capacity left, and competitively priced LNG will continue to flow from these well-placed sources. The situation is, therefore, convoluted and dynamic for all players.

Deciding on requirements in Annual Delivery Programmes (“ADPs”) will be more complicated, and typical multi-period optimisation tools will confirm the problem without necessarily providing a good solution. As always in the gas industry, the flexibility challenge is amplified by requirements to balance interests of multiple parties, and the use of rights to unused capacity. Companies will tend to stay with their full entitlements, do swaps or secondary sales if possible, and take the chance that things will work out at the end. In fact, as seen several times in 2016, it is likely that final delivery programs and penalties increasingly force cargo loadings on ships that sail without a stated end destination. Fleet capacity requirements rise significantly as a result, and we have examples of 20 percent overcapacity.

The ability to play strategically on logistical and offtake flexibility with storage is limited to very few companies, notably in Europe, Japan and Korea. It is hard even for these to design and execute flexibility programs, and capacity decisions tend to try to limit cost. Capacity may also be misplaced in relation to concrete requirements. A flexible new value chain concept must, therefore, be developed, along with commercial adroitness and organisation to scale, and suitable new systems and tools. While some companies already demonstrate expert capabilities at complex balancing and logistics, a simple Excel-based level of analysis is surprisingly prevalent.

Our base scenario is that in the interim, many companies will gamble on ultimately being able to place LNG volumes in the spot market. Lacking suitable market flexibility tools, many cargoes will effectively go into slow-steaming floating “operational storage” until an opportunity emerges, to the extent fleet capacity (and LNG quality) allow.

The capacity of the market to handle many such “free” cargoes simultaneously has not yet been tested on scale, but some smaller buyers already seem to have adopted an opportunistic strategy – and profited. From 2016 there is well documented evidence that some US cargo cash margins were substantially negative, and the true cost for the capacity holders only becomes know after the fact.

Difficult Resolution: Can the Tipping Point be avoided?

Can established markets give a life-line to larger volumes of surplus LNG? Theoretically, Europe and China together have spare regasification capacity to absorb all new LNG capacity coming on stream in the next three years. Many in the industry have described Europe as the global balancing market for LNG, and the completion of several major system connections and reinforcements, for example between PEG North and South in France, makes the European market physically better able to handle LNG more flexibly and thereby compete with pipeline gas and coal on a commercial basis.

Ultimately, however, LNG is not as flexible as pipeline gas, and volumes must be planned at least 1-3 months in advance. The sale of distress LNG cargoes will, therefore, tend to be at the mercy of the buyer. Realistic and disciplined forward planning is likely to be key to successful volume placement the next three years.

In the converse, there is a scenario where incremental oversupply will meet a market barrier and trigger a price change, resulting in a low price that could persist. Such changes are typically triggered when volume imbalances systematically exceed about two percent, or clearly, exceed the market’s balancing capability. For example, Europe’s actual ability or willingness to absorb excess LNG has often been systematically overestimated. As noted earlier, this seems to be due to insufficiently deep gas value-chain integration of LNG and unrealistic expectations by some players.

With constrained market access, weak transparency and ineffective price discovery, a significant marginal LNG price drop is probable. If LNG projects remain on track, and volumes hit markets by surprise, there is a real probability that large price changes could be triggered within 12 months. The late winter or spring of 2018 appears to be the start of this critical period.

Regional market conditions define what it takes to sell incremental gas, while logistics and market volume response time for absorbing larger volumes of LNG complicate the picture. The looming question is if markets will be continuously unsettled by distress cargos or if lower prices could actually drive LNG supply contraction. Prices drive supply responses in merit-order competitive markets, and it will be a key test of efficiency if and how the LNG market will curtail capacity, or how quickly exposed players learn to manage LNG balancing on the global level with necessary regional finesse.

Business Implications: Proactively Managing Supply and Demand

What can a company facing a balance mismatch and an offtake challenge do to succeed? Since it is difficult to imagine that LNG markets will be as logistically efficient as other energy markets, a company cannot rely solely on market mechanisms. The value chain and capacity system for each company has to be bespoke, and certainly different from earlier. Ultimately, it comes down to a practical question packaged in “cargo units”, global dynamic logistics and defining tolerable levels of risk. Like in other competitive markets, asset portfolios will have to be realigned continuously, in particular focusing on value chain capacity management.

Global operations may require scale and diversity that benefit larger companies. Regionally focussed companies may, therefore, find it difficult to operate globally, and risk losing focus by doing so. Partnering through joint ventures are conventional ways to overcome challenges of global operations, but integration can be difficult. Some recent well-published joint ventures or partnerships may not sufficiently address emerging operational challenges and will probably face difficult principle decisions.

We see seven key management responsibilities going forward:

- Assessment of required scale and natural geographical scope of operations

- Establishment of a balanced asset base and logistics capabilities for fast reallocation

- Selection and development of capable and high-fit partners and counterparties

- Definition and implementation of suitable operational tools to support capacity decisions and operations, including multi-period portfolio planning

- Performance gathering and processing of multi-source global LNG and gas market intelligence

- Organisation and process design for integrated value-chain operations

- Clearly defined risk management measures and policies

These decisions will benefit strongly from a broad-based management visioning exercise, such as “LNG 2030”.

To summarise, increased business adroitness with deep and flexible storage and modulation capabilities for the 1-12 month horizon are the key capabilities that will characterise LNG operators in the years ahead, whether the focus is global or regional.

The Next Phase: Positioning for Future Development Challenges

Increased flexibility will greatly facilitate the development and execution of annual LNG delivery programmes, and also make it possible to define and optimise the long-term business direction and portfolio. Already, there is a drive to seek commitments for the next wave of world-scale LNG project developments. These project development processes will be difficult in an environment of surplus LNG.

While much attention is on US-based projects, US sourcing should not be overweighted. Other operations are increasingly interesting in a global logistical scheme. With a 3-6 year horizon for project development, which is historically rather short, the future sourcing structure is very much a question for today.

On one side, successful new projects will need to present a very attractive cost level, and involve developers with an excellent track record. On the other side, buyers will carefully balance and select primary upstream sourcing with their chosen mid- and downstream commitment and flexibility requirements. It is easy to be tempted to adopt a growth strategy in the current market and so make extensive commitments, but that temptation should be seen against the likely development of gradually more merchant upstream operations.

The LNG industry now enters a phase of value realisation. If this value realisation is threatened in the years ahead, coming projects will find it difficult to find the foundation buyers that the industry has been built on. It is also much too early to say when or if the LNG market can develop qualities that make it possible to envision purely merchant plant developments based on external project lending.

Eikland Energy & Enerdata Singapore – Business Intelligence and Strategy Advisory

For further information about the services and specific issues raised in the analysis presented here, please contact Kjell EIKLAND (kjell.eikland@eiklandenergy.com), MD Eikland Energy or John HARRIS (john.harris@enerdata.net), Head of Gas, Enerdata Singapore.