Reflections on Europe and natural gas after 90 days of Russia’s war in Ukraine

90 days into the Ukraine conflict, Europe is seeing a powerful revival of small and large natural gas projects that were mothballed or even scrapped as little as a year ago for lack of commercial interest or environmental opposition. The fear that natural gas would suffer the hydrocarbon atrophy in Europe has been replaced by a clarity of vision and force of action that only a real crisis can produce.

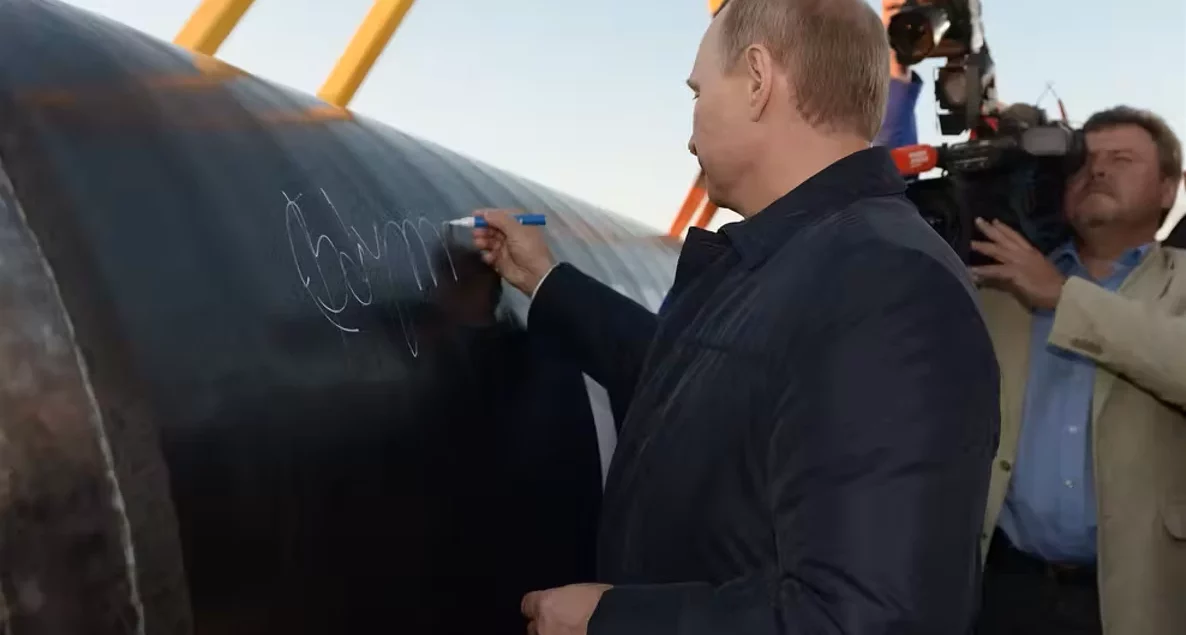

The decisiveness of the EU and each member is directly proportional to both the dependency on Russian energy supplies and potential territorial threat. In a major strategic and tactical gaffe, Vladimir Putin’s overstretched territorial ambition and highly visible 90-day force buildup not only ruined his chance of success, but also created a broad historic schism that closed the post-USSR era.

In energy alone, little did he apprehend that the convolution of massive expansion of LNG projects worldwide with cargo flexibility, harmonized quality standards and open access terminals would undermine the market power he coveted. The costly wave of renewable power project developments and conservation measures in Europe is now also fully vindicated, despite the too zealous early dismantling of nuclear and coal power plants.

What now seems to be a nightmarish energy situation for Europe is rather a tactical – albeit relatively painful – operational change to ambitions and plans that were formulated clearly as early as in 1998. The first EU energy directive. The energy intensity of the economy has declined consistently for decades, and the flexibility of the supply infrastructure is greater than ever.

Putin himself laid the foundations for this on 1 January 2009 with the 13-day stop of gas exports to Europe via the Ukraine. The 2011 EU directive on the implementation of gas grid interconnections and reverse flow capability was a direct result of the embargo. Even the Ukraine can receive gas from the west. The projects are now largely completed and in 2021 the main grids in the north and south of France where connected.

What we see today, 90 days after the invasion, is that uniform crisis-level natural gas prices throughout Europe are now concentrated to the most supply-exposed regions, such as Germany, the Netherlands and Italy. Insufficient gas export capacity from the UK and Southwest Europe to Northwest Europe prevent TTF prices to fall to the now much lower prices in the UK and Spain. Here there is ample LNG import capacity available and renewables production is strong. Market mechanisms work, and supply and demand adjust.

Energy price indexation is a very important aspect of the price dynamics that we have seen in the past two years. From the extreme trough in May 2020 to the extreme peaks in March 2022, there is only one approach that follows demand and can easily survive arbitration: price in market of the user. However, the recent extreme variability is unsustainable for many end-users. As a result we are likely to see an increased interest in both longer-term contracts and blended time-averaged contract prices. Gas sellers and buyers will have different views and requirements, but with the generally higher price levels we expect ahead we expect them to look beyond the current situation and converge.

Unfortunately, Northwest Europe is likely to face crisis-level prices for at least another year and be exposed to continuing risk of Russian gas delivery reductions. Only when all six FSRUs are in place (4 in Germany and 2 in the Netherlands) are natural gas prices (and by extension, electricity) in our view likely to converge to UK and NBP price levels again. The accelerated completion of missing interconnection links, reinforcements, and storage fill obligations will gradually bring control over the situation.

However, Russian gas supply uncertainty may in fact increase over the next months with increasing frustrations as the war in Eastern Ukraine fails to resolve and with sanction effects taking hold. The former may be met with well-stocked European gas storages ahead of the winter, while technically driven supply availability curtailments, for example by not being able to service LNG liquefaction train gas compressors or gas pretreatment equipment, could possibly be balanced with LNG diversions or new production capacity coming on stream elsewhere.

The big energy-related questions about future direction are therefore not about Europe, but Russia. “Quo ad proximum“, where go next, Vladimir Vladimirovich? After this 90th day of war, Russia appears to have acknowledged the schism with Europe and Lavrov expresses that the future lies with China. That is both rhetoric and a branch of hope, but possibly also a request for a lifeline. Most Russians have no interest in China, and would much rather vacation in Europe. Putin’s current strategic blind alley can probably only end with him.

A growing flow of US LNG to Europe is no panacea for Europe either, and there will be a new focus on risk balancing and energy diversification. While current energy prices give a cash flow for energy companies that can literally finance anything, corporate strategies must see ahead to require a strict payback period. Already, the European direction is being reinforced with new sustainability and energy efficiency requirements that lock to the path to 2050 even stronger than before.