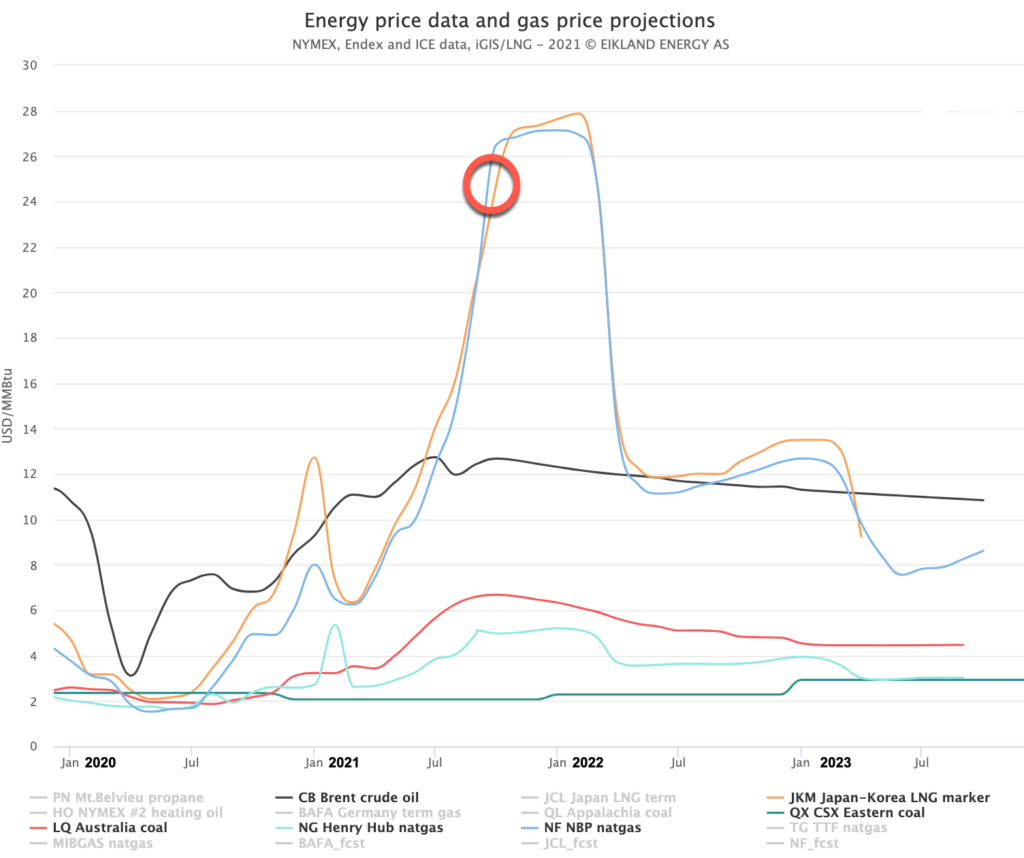

European natural gas prices have literally risen exponentially since May 2020 (sauf a winter bump), and are now at 23 USD/MMBtu, a massive 75% over crude oil parity and 3x over our reference level. In the past week media attention has blossomed as winter is finally showing up in northern Europe. At the same time US Henry Hub prices have also increased, but only to 5 USD/MMBtu, its typical ceiling level. The market presently “expects” this state to last until spring 2022 with aftereffects into 2023 and even beyond.

Most commentaries miss key factors in explaining the European situation, claiming that limited renewables production, low storage levels and strong Asian LNG demand are to blame for high gas prices. There are also vague references to Covid-19. European renewables power output has in sum in fact been roughly normal, with very strong solar production through the summer. EU gas storage levels are below average for the season, at 65%, but in the big picture still providing adequate buffer and flexibility for a normal winter. And the healthy Asian LNG demand has not challenged global production capacity.

In our view there are five dominant “root cause” reasons for the price rise:

- The aftermath of construction restart of the twin Nordstream 2 pipelines on 15 January this year,

- Well-known temporary supply reductions at several LNG plants,

- The opening of the Northern Sea Route to Asia that has seasonally removed significant tradable LNG volumes and liquidity from the European market,

- The indirect consequences of the fire at the Melkøya LNG gas turbine 4 on 28 September last year, and

- An overcommitment of LNG buyers, considering the demand drops caused by Covid-19, that in turn caused many companies to be over-prudent in 2021 and ultimately having to rely on spot purchases.

The fifth reason nearly caused bankruptcy of several companies, such as JERA. In Europe, the market sophistication and portfolio planning tools should in principle have mitigated many of these complications, but there is evidence that they have not, and we will revert to this.

Some plants have in parallel experienced temporary supply-related curtailments, such as at Atlantic LNG, Peru Melchorita LNG, NWS LNG, and the repair of known component failures at Gorgon. Covid-19 has also caused delays in equipment deliveries and installation. In sum, this fourth reason resulted in non-trivial additional short-term reductions of LNG output in 2021.

The NSR is in practice now open for Arc-4 class ships for 4 months of the year – July through October. This has lately removed significant transshipment and retradable volumes for Europe but will at least this year revert by November and certainly by December. The January/February 2021 tests of mid-winter NSR passage with two Arc-7 LNG ships left one of them damaged, despite ice-breaker assistance, and it had to return via Singapore to be repaired at Damen, Brest in France.

It is also worth mentioning that the Panama Canal is effectively “full” and does not permit more than 4 LNG carrier transits per day. Last winter, Panama Canal waiting times became a major observable, but the industry has now largely adapted to this constraint.

The result has become a reweighting on Europe and Indian Ocean market destinations. Pakistani LNG auctions show how a lack of long-term contracts can radically push up LNG spot prices, but secondary trading also illustrate how radically ships can change course and destination in the Mid-Atlantic. Volumes are available, the question is who has the most flexibility. That used to be Europe.

The fourth reason, the Melkøya fire, is perhaps the most surprising factor, since it is an example of an industry insider matter that rarely gets public attention. This time it has become very well documented by media and through the report by the Norwegian safety regulator. The fire was caused by self-ignition of leaked oil in a dirty and hot air filter. The oil flow turned out to be unstoppable and fire extinguishing equipment could not be directed to stop the fire.

LNG liquefaction plants are all giant refrigerators with compressors predominantly driven by natural gas-fueled turbines. The design flaws exposed at Melkøya and the experiences of the reputable operator widely scared manufacturers and other operators globally to order extraordinary plant risk assessments and corrective measures. We assess that some of this work is still ongoing, in part delayed by Covid-19, but strong flaring activity has signaled LNG plant testing and startup activities for several weeks now.

The availability of spot LNG cargoes dropped because of these five factors, and global LNG output has been well below 2019/20 levels for most of 2021. Spot gas prices therefore did not drop significantly as normal during April and May but continued an exponential rise – still relatively modest at the time – into the summer and early fall.

For Europe, despite being nearly price-neutral with Asia until recently, a slight JKM-TTF positive spread led to a combined reduction in LNG supply of about 25 BCM in 2021 to now. Had these volumes been delivered, European gas storages would now be full. Perhaps a return to a larger share of longer-term LNG contracts could be an outcome when the current situation has calmed.

But the most striking factor is the deep problem of Nordstream 2. Its potential gas supply into Europe of up to 60 BCM per year equals 8 modern world-scale LNG plants and could replace any annual LNG supply volume to Europe, past or present. Therein lies the pipelines´ obvious political interest as well.

With the resumption of Nordstream 2 pipeline lay of the short remaining segment across Danish waters, and with signs of Realpolitik from Biden´s Washington, not only did market players see that Russians reduced bookings and flows via Ukraine, European players on their side also felt less need for LNG. In fact, it appears that players did not hedge their bets in volume planning and took rapid pipeline permitting and startup ahead of winter 2021/22 for given.

They were wrong, and though the summer a clear conflict between Gazprom and EU pipeline ownership and capacity separation principles manifested itself. Gazprom appears to have fully expected to start operations with the traditional speed of such matters, seeing the construction permit as implying permit for commercial operations. The “truce” in the geopolitical conflict between the US and Europe was found in enforcing the EU open access model, as revised in 2017, for Nordstream 2 and a compromise on Ukraine.

As it currently stands, we face a “situation” – i.e., lack of gas – caused either by a Gazprom decision to play hardball with the EU Commission and the German regulator, or that both Gazprom and European players have severely misjudged regulatory complications and political climate. Maybe both. We are now seeing the results in persistent low Russian gas exports, extreme gas prices and attempts to bring additional LNG to Europe.

Whatever the cause, LNG production is now slowly ramping up again and projected LNG inflow to Europe is picking up. Some short-term relief is also coming from major industrial gas feedstock users that now simply turn down production or even close plants.

Remarkably, LNG ship dayrates have been rock steady throughout this period, highlighting that global LNG output has in fact been relatively low this year. New US LNG plants at Sabine Pass and Calcasieu are expected to enter production this fall, Russia´s smaller scale Yamal train 4 finally seems to have output, and now Portovaya finally appears ready as well. There is even evidence of activity at Yemen´s Balhaf plant and today Equinor confirmed that they were on track for March 2022 restart of Melkøya LNG.

Major uncertainty remains, perhaps concentrated on the issue of Nordstream 2 final permitting and Gazprom´s stance. More than normal, only winter will tell. Between rapidly changing fundamentals and the interplay of Realpolitik and popular politics, prices can also tumble.