From Henry Hub plus to LNG netback pricing – The rapid change, background and implications for the LNG market – A pink-paper

In the spring of 2019 natural gas prices converged to marginal equality world-wide for the first time. This was due to sharp supplier competition with the backdrop of substantial new LNG production capacity, a mild winter and insufficient marginal demand from the power sector. The new low price level has brought effects that are likely to last, displacing “Henry Hub plus” LNG pricing by market value netback pricing.

While futures markets do not yet reflect this assessment, Eikland Energy believes that the new prices now seen are natural developments that brings operational convergence with price formation in other open energy markets. They also mirror price terms in recent LNG contracts. This note discusses the situation and outlines implications for players and the market, in particular the need to reassess portfolio risk exposures.

THE BACKDROP

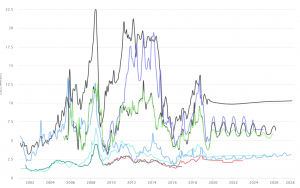

US shale gas plays have put persistent heavy pressure on Henry Hub gas prices and attracted gas buyers globally to US LNG projects since 2011. The promise of guaranteed LNG feed prices below 5 USD/MMBtu appeared to be an unbeatable business proposition compared to other LNG sources. The moratorium on nuclear power after Fukushima accentuated the momentum.

This picture has now changed, and new US LNG projects have found it difficult to attract buyers based on Henry Hub LNG feed gas prices. Oversupply and lower international field development costs have undermined the competitiveness of US LNG.

The domestic US market for natural gas does not offer any help. It is now largely saturated as a result of low prices over many years and continuous reduction in specific energy use for heating and cooling. Natural gas prices are at a coal parity level that effectively allows gas to be competitive in all uses. Ultimately, this minimal price has made gas demand non-responsive to further price declines.

US producers therefore face the precarious situation that domestic natural gas prices can fall significantly if they increase gas production. In the Marcellus shale gas play, for example, local oversupply caused by lack of pipeline capacity have shown that prices can drop to 0.50 USD/MMBtu. This is the marginal cost of lean shale gas production.

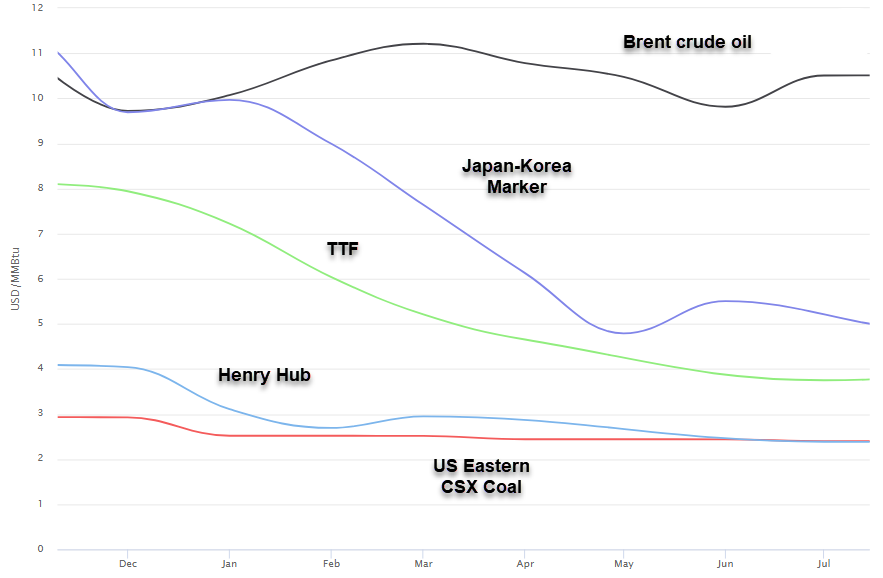

THE PRICE DROP

The winter of 2018/19 turned out to be 5-8% milder than normal in both Asia and Europe. Full production from five new 5+ mtpa LNG trains, resulting in a capacity increase of nearly 10%, contributed to significant oversupply. Nuclear plants in Japan restarted and electricity production from renewables dented gas demand in many countries. In sum, the global LNG market did not offer the expected price support, and multiple negative forces coalesced to bring down prices substantially.

Several long-term capacity holders from LNG projects found that markets did not need the LNG cargoes they had committed to taking under the annual delivery programs. Loaded ships alternatingly targeted Asian and European buyers as global prices wobbled down, week by week, in response to oversupply. Some astonishing ship journeys showed that even the largest and most professional companies had trouble.

One very recent such journey is shown below, the Diamond Gas Orchid that left Wheatstone LNG, Australia on 19 May and eventually discharged at Hainan, in the south of China after attempting destinations in North-East Asia. (The computed return journey to Darwin from 20 June is shown in red.)

Such ship journeys started as early as mid-January and forced to discharge unwanted LNG, prices fell. By the end of May prices had found the pure marginal cost level, weakening even Henry Hub prices by 10% in the process.

IMPRESSIONS vs. FUNDAMENTALS

While an LNG oversupply situation had earlier been expected for the 2019-2022 period, the fear seemed to vanish after Shell released its bullish LNG demand outlook in February 2018, and the importers’ association GIIGNL in April published strong global LNG import data for 2017. Subsequently, major final investment decisions have been made and several more are expected later in 2019. The price developments in the spring of 2019 took the market by surprise, and many companies still the drop as extreme, but still routine seasonal movements. Futures prices still corroborate this view.

Eikland Energy, however, believes that the price development has broken new ground, requiring a recalibration of expectations.

The US potential oversupply predicament is exacerbated by the success of developing highly productive multi-tier Permian basin shale resources. Shale oil is the real revenue generator, but significant volumes of associated gas need to be marketed to release this value. Gas flaring is prohibited as a routine disposal method in all US, and Permian shale resource development will be curtailed unless new outlets for gas can be found. Since the US market is saturated, the export market appears to be the only near-term option for key producers. Pipeline exports to Mexico stand to increase significantly, but US resources far exceed the expected export level. Marginal shale development costs are only expected to start to rise after 2025 as the pool of the best locations are depleted.

NEW LNG CONTRACTS SUPPORTING PRICE CHANGE

It is in this context that Apache Corp. recently signed a contract with Cheniere for 15-year dedicated supply of 0.85 Bcf/day of natural gas to Corpus Christi LNG train 3. The novel aspect is that the price is based on netback from realized sales of LNG in the global market. The associated gas volumes are therefore removed from the US market and price dynamics through a bi-lateral arrangement. For Apache the contract with Cheniere allows a planned development of a major new tranche of its Permian shale resources. Apache has effectively created a direct virtual pipeline to the international market with maximum volume security while accepting global LNG price risk.

There is naturally more to the contract between Apache and Cheniere than what is released publicly. It is unclear, for example, if the associated Cheniere netback sales portfolio will be based on spot trades or if longer-term contracts at different prices will also be included. Additionally, both the yet unknown cost attribution principles and levels for liquefaction and shipping are important. US gas/LNG contracts are typically relatively simple and uncertainties about other contractual matters do not diminish the significance of Apache’s acceptance of global price risk through the netback price principle.

In fact, US gas producers and LNG sellers have recently also accepted LNG sales contracts based on Asian JKM and European TTF price indexes. The implied price principle is that producers accept the value of natural gas in the market of the final buyer. The netback model will typically be combined with FOB terms, while the market price index model is a CIF/DES version. It is not known if any of the market-based contracts signed thus far contain price formulas with floors and caps, or pass-through factors, to limit extreme upside or downside risks for any party. The presence of such terms will typically depend on the symmetry of risk capacity between buyer and seller on a case-to-case basis and would conventionally also include a price review clause. This would be unlikely in a modern US gas contract.

BUSINESS RATIONALES

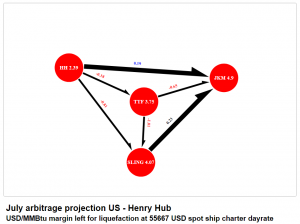

The latest data shows that full-cost natural gas netback price (or value) at the US LNG plant gas meter is substantially negative at the prevailing June/July 2019 global natural gas and LNG market prices at a band around 4 USD/MMBtu. By comparison, Henry Hub prices are presently around 2.40 USD/MMBtu. The picture below shows the estimated July liquefaction contribution margins for alternative trades per the latest JKM trading day in June (unadjusted for higher Asian spot ship day-rates).

Apache apparently expects to realize most of its sales proceeds from “bundled” crude oil sales. Their upside is that they will then earn maximal profits during high-price periods. In such a pure model, Apache would require full volume certainty, i.e. with no volume risk. They then absorb fully allocated LNG liquefaction and shipping costs and take full market price risk on a fully wrapped project basis, with no special corporate balance sheet exposure. In fact, Apache could even be considering packaging this full value chain “pure asset” shale structure in a separate investment vehicle.

In this picture of structural price and contracting changes driven by radically lower LNG prices it is highly surprising that Polish Oil and Gas Company (PGNiG) in June 2019 signs a 15 year 1.5 mtpa FOB contract with Venture Global based on Henry Hub indexing, from the Plaquemines project. The circumstances for natural gas in Poland are extremely politicized, however, and the contract with Venture Global project is stated to be linked to the expiration of a Yamal contract with GazProm. Yet, much like India’s GAIL at Sabine Pass earlier, PGNiG are under recent price trends likely to find this contract with Venture Global increasingly difficult to live with. There is simply no tradition for risk-sharing, price review or market-out clauses in US LNG sales contracts based on Henry Hub indexation. While FOB terms give PGNiG some disposition flexibility, claimed benefits are often not realized. In contrast, neighboring Lithuania has settled on more pragmatic short-term US sourcing arrangements.

As mentioned, the US gas market is effectively saturated and only international markets appear to offer producers outlets for the significant volumes being considered. However, the 50% decline in LNG prices from early 2019 has come as a surprise to most players. The current price levels in both Europe and Asia now reflect Henry Hub gas prices plus fully marginal liquefaction and LNG shipping costs. The current price balance point is achieved by European and Asian gas prices indirectly being determined by the prevailing merit order intersection point of US coal and gas power plants. In short, LNG prices are set by coal prices into US power plants which also happens to boost competitiveness of natural gas against coal in local European and Asian markets.

NEW PRICING FRAMEWORK vs. PRODUCER INTERESTS

Analysts may be confused by the observation that the current low prices still fundamentally reflect a Henry Hub “cost plus” model. It just happens to be on a competitive marginal cost basis. This is a normal duality phenomenon from economic theory. The price picture will get even more complicated as the netback pricing and end-user market price index pricing models take operational hold. This means that the current price floor at roughly Henry Hub plus 1.50 USD/MMBtu potentially can be further lowered. The benefit is that such a marginal change, in part also connected with rising emission costs, stands to trigger a demand increase for natural gas in the power sector, displacing coal outside of the US. In fact, this is the marginal value of the only real growth segment for LNG.

However, a schism of interests is now being created between dry Marcellus shale gas and rapidly growing volumes of associated gas from Permian shales. As long as the US market and Henry Hub prices are protected, many producers will be happy to accept lower netbacks for gas sales internationally as long as shale oil production is unhindered and can generate required returns. Such differential pricing is also a classic trait of international trade, occasionally claimed to result in unfair competition. The implications for the global LNG market are significant, and Apache’s Permian Basin shale gas disposition logic and acceptance of market netback pricing are likely to be extensively copied. Many buyers are also shifting their sourcing focus to Texas and Permian gas. Internationally, this means that a new price level and new global price post-Henry Hub convergence framework could be in the making.

STRUCTURAL CHANGE OR JUST A BLIP?

What is the likelihood that the current price level is merely temporary and seasonal? Firstly, there appears to be a structural surplus. It appears likely that LNG supply will continue to outpace near-term demand, with a stack of further proven potential gas supply waiting for market opportunity. Much of it is “free” associated gas. Even in the face of depletion of many legacy gas supply contracts there is no immediate structural deficit of natural gas supply as a series of large gas pipelines and new LNG trains enter production. The size of the supply wave is tremendous. Eikland Energy expects the current risked project portfolio on average to enable one 5 mtpa train (or equivalent capacity) to enter production every quarter to beyond 2025.

Secondly, a key reason for the current low prices is that LNG projects practically have little output flexibility. The limited LNG storage and the yoke of annual lifting/delivery programs effectively force flat output outside of scheduled maintenance periods. This leads to a focus on cargo placement and cargo-level global arbitrage hunting instead of early choice of a market with modulation through more complex underground storage strategies. The effect is that prices are subject to a continuous squeeze even with moderate volume surplus. Given the volume outlooks, and as seen this spring, periods of deep marginal prices may become normal. On average, LNG prices may be expected to lie in the 5-10% range against Brent for several years ahead.

CONSEQUENCES FOR LNG CONTRACT PORTFOLIOS

The implications of the structural change in price formation are substantial and have the potential to play out quite dramatically over the next few years. The first mover buyers of US LNG are locked into Henry Hub terms and contract terms do not provide for renegotiation, not even based on unmarketability of the LNG. These buyers no longer control their markets as many of them once did. With a continuation of the new pricing regime that took root this spring it is possible that some companies must write off unrecoverable LNG capacity payments. It is also entirely possible that some particularly exposed companies will see bankruptcy or restructuring as the only way out.

LNG contract prices have always had to adjust to market realities. For example, in 2004 the Tangguh project was signed at 10% of Brent, capped at 38 USD/Bbl, while post-Fukushima projects were signed at euphoric 14.8% and higher when the Brent price was over 100 USD/Bbl. Some shorter- term contracts even exceeded crude oil thermal parity at 17%. However, subsequent renegotiations in the aftermath of the 2014 oil price decline have brought many key LNG contracts to around 12% of Brent, which is also reflective of the historical European oil-linked gas contract. Recent price volatilities highlight how difficult it is to find the right balance between short-term and long-term contracts in the LNG sourcing portfolio. Traditional opportunities for price reviews every five-years in oil-indexed contracts are getting ever harder to manage in the face of commercial realities.

INCREASING MARKET EFFICIENCY AND SHIPPING OPERATIONS

Despite the initial convincing economics of Henry Hub pricing it was ultimately not a robust pricing principle for liberalized open gas markets. The further LNG volume growth and completely dynamic movement of cargoes means that standard market economics and principles will apply. It the logical endgame this means a convergence towards local market LNG valuation with cargo flows increasingly tending to minimum cost solutions over time. Current contract structures will significantly bias optimal flows for possibly many years ahead, but there are already significant LNG volumes, possibly as much as 20% of the market, that will ensure effective pricing and flows.

What do these trends mean for LNG shipping? Stated a little flippantly, shipping is a mode of energy transportation that just happens to be very slow and bulky. This is a disadvantage that must be minimized. However, the recent growth in dynamic global LNG trading has required additional shipping capacity which has reduced utilization rates, added costs and inefficiencies. While this may be positive for ship-owners, the fragmentation and inefficiencies are fundamentally unsustainable for the longer-term growth and market development.

As it is presently, LNG shipping modes add barriers to market development, efficient arbitrage and pricing that benefits no one. Eikland Energy believes that the key conceptual challenge ahead is to develop LNG transportation chains that effectively allow long- and short-term capacity booking that is as routine as it is in other energy markets. Recent work suggests that much is likely to be gained simply by rewriting LNG shipping roles and responsibilities in terms of classic natural gas transportation system analogies. The physical elements are largely already in place.

CONCLUSIONS

LNG has risen to a global energy force in the course of just a decade. The next step that is now being unleashed in pricing and operations will be the convergence into energy markets at large. The experience from structural changes in energy markets is that change takes place much faster than initially expected. This includes the kind of changes to pricing that are now being observed in LNG.

The main conclusion from the assessments in this document is that companies should lose no time in assessing their business and risks going forward from the perspective of the next level of deeply integrated energy markets with prices converging at marginal levels. Current portfolios and investment decisions must be tested against the effect of the price formation dynamic that took hold this spring.

For further information, contact Eikland Energy at contact@eiklandenergy.com or DID +47-9951755.